New report: Climate Collateral

How military spending accelerates climate breakdown

Authors: Mark Akkerman, Deborah Burton, Nick Buxton, Ho-Chih Lin, Muhammed Al-Kashef

A new report by the Transnational Institute, in collaboration with Stop Wapenhandel and Tipping Point Noth South, and with GCOMS as a co-publisher, shows that military spending and arms sales have a deep and lasting impact on the capacity to address the climate crisis, let alone in a way that promotes justice. Every dollar spent on the military not only increases greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but also diverts financial resources, skills and attention away from tackling one of the greatest existential threats humanity has ever experienced.

You can download it here.

Executive summary

As the world’s climate negotiators gather for their annual summit (COP27) in Egypt, military spending is unlikely to be on the official agenda. Yet, as this report shows, military spending and arms sales have a deep and lasting impact on the capacity to address the climate crisis, let alone in a way that promotes justice. Every dollar spent on the military not only increases greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, but also diverts financial resources, skills and attention away from tackling one of the greatest existential threats humanity has ever experienced. Moreover, the steady increase in weapons and arms worldwide is also adding fuel to the climate fire, stoking violence and conflict, and compounding the suffering for those communities most vulnerable to climate breakdown.

The trajectory of military spending and GHG emissions are on the same steep upward curve. Global military spending has been rising since the late 1990s, surging since 2014 and reaching a record $2,000bn in 2021. Yet the same countries most responsible for large military expenditure are unable to find even a fraction of the resources or commitment to tackle global heating.

Our research reveals the following:

The richest countries most responsible for the climate crisis are spending more on the military than on climate finance

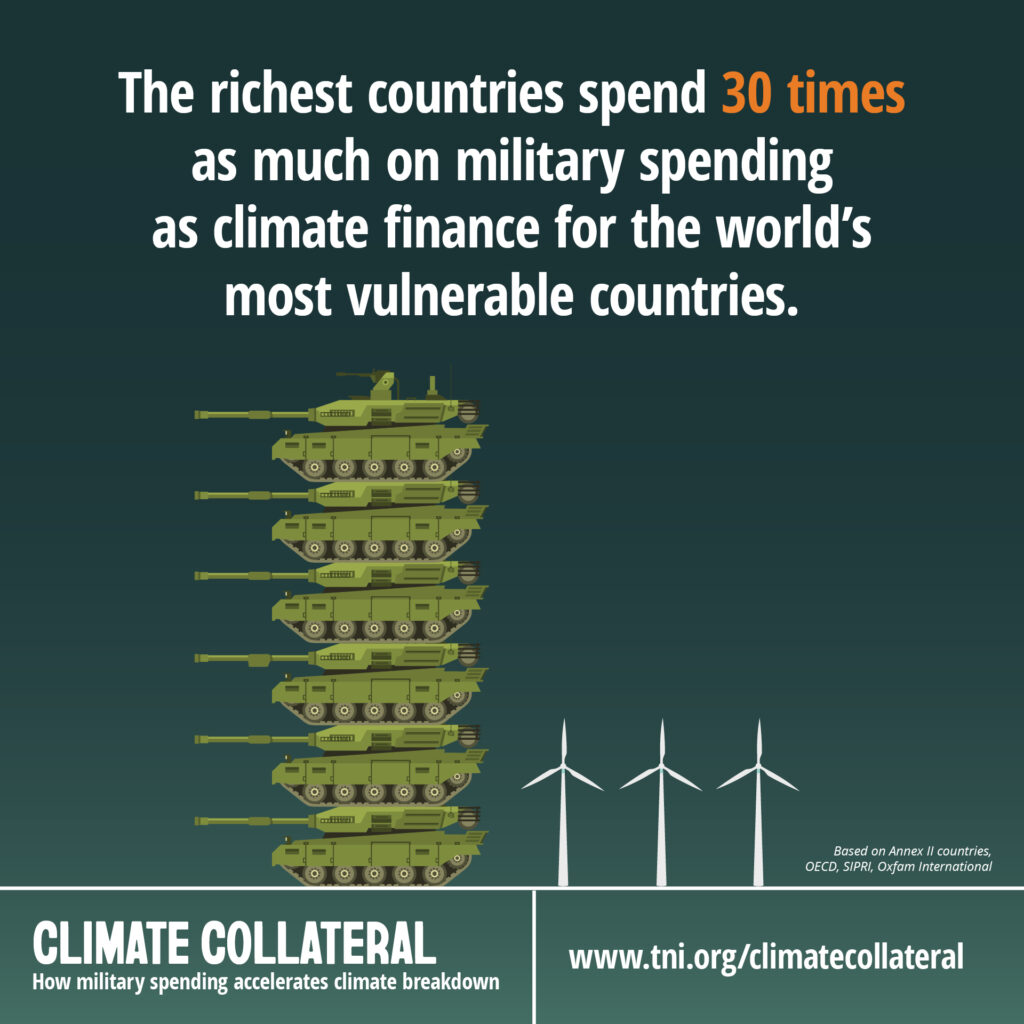

- The richest countries (categorised as Annex II in the UN climate talks) are spending 30 times as much on their armed forces as they spend on providing climate finance for the world’s most vulnerable countries, which they are legally bound to do.

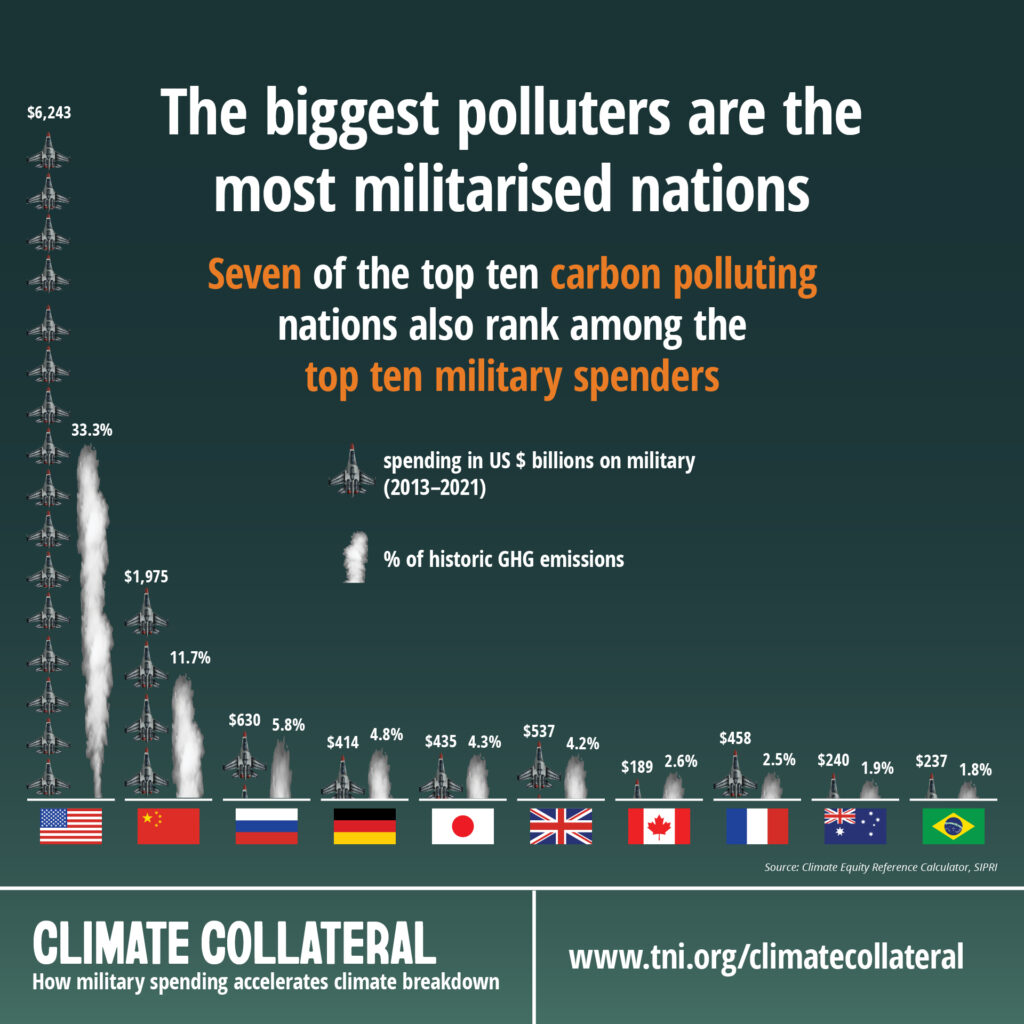

- Seven of the top ten historical emitters are also among the top ten global military spenders: in order of magnitude the United States spends by far the most, followed by China, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, Japan and Germany. The other three of the top ten military spenders – Saudi Arabia, India and South Korea – are also high GHG emitters.

- Between 2013 and 2021, the richest (Annex II) countries spent $9.45 trillion on the military, 56.3% of total global military spending ($16.8 trillion) compared to an estimated $243.9 billion on additional climate finance. Military spending has increased by 21.3% since 2013.

Military spending increases GHG emissions

- A 2020 report by Tipping Point North South estimated that the carbon footprint of the global militaries and associated arms industries was around 5% of the total global GHG emissions in 2017. By way of comparison, civil aviation accounts for 2% of global GHG emissions.

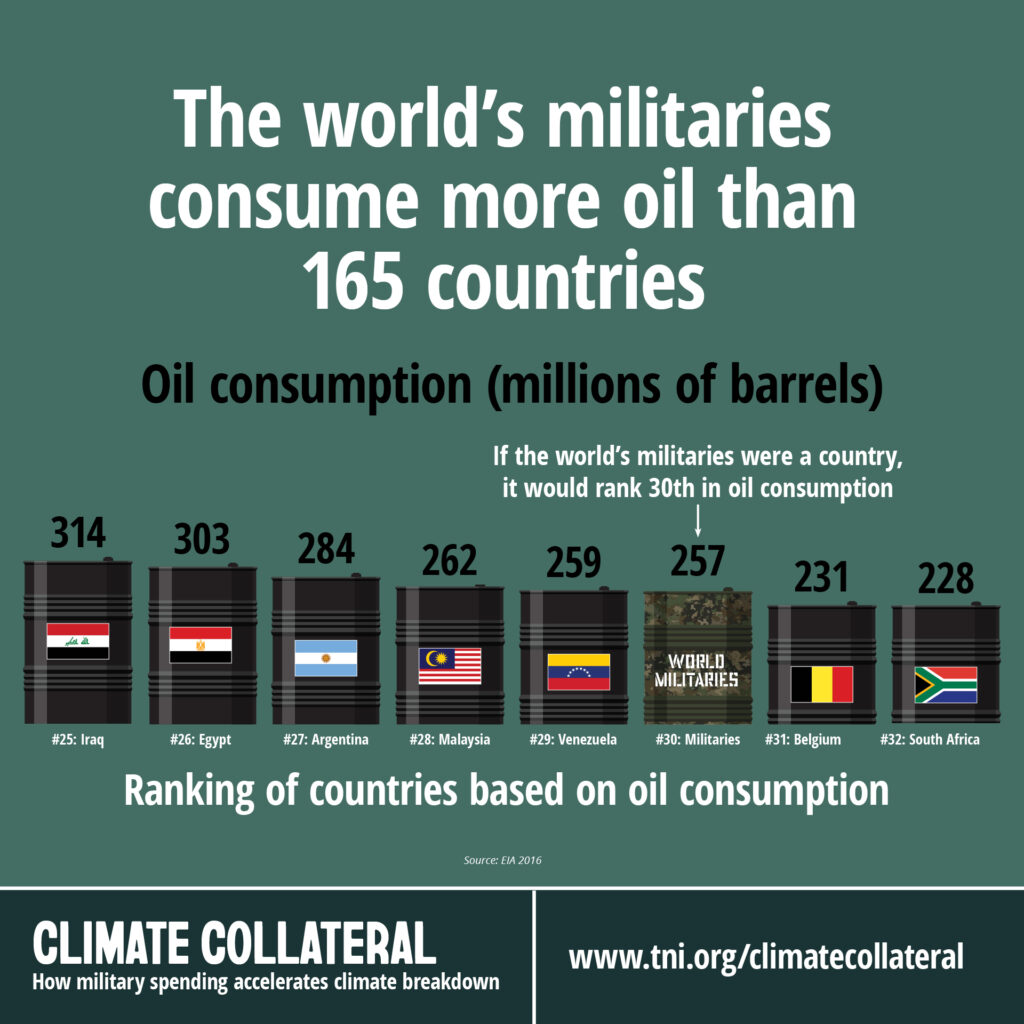

- In terms of fuel consumption, if the world’s armed forces were ranked together as a single country, they would be the world’s 29th biggest oil consumer, just ahead of Belgium and South Africa.

- Other estimates by CEOBS and Scientists for Global Responsibility (SGR) put the annual military carbon footprint at 205 million tonnes for the US and 11 million tonnes for the UK of carbon dioxide equivalent, with France accounting for about a third of the European Union’s estimated 24.8 million tonnes.

There is no evidence that the military can be green

The armed forces of the richest countries increasingly boast of their efforts to address climate change, pointing to the installation of solar panels on bases, preparation of sea-level defences, and replacement of fossil fuels in certain military hardware. A closer look, however, suggests this is more hype than substance:

- In most national military climate strategies, reduction targets are vague and undefined. The UK’s 2021 Defence Climate Change and Sustainability Strategic Approach, for example, sets no reduction targets apart from ‘contributing to the achievement of the UK legal commitment to reach net zero emissions by 2050’.

- The military has been unable to find adequate fuel alternatives for the transport and equipment used in operations and exercises – which make up 75% of military energy consumption. Jet fuel alone accounts for 70% of the fuel used by the military, followed by naval propulsion and, to a lesser extent, land-based vehicles. The military faces the same challenges as the civilian aviation sector – alternative fuels are still too expensive, limited in availability and unsustainable.

- Most of the stated goals of ‘net zero’ are based on false assumptions – reliant on technologies such as carbon capture, that as yet do not exist at scale, or dependent on alternative fuels that have serious social and environmental costs.

- Meanwhile the military keeps developing new weapon systems that pollute even more. For example, F-35A fighters consume about 5,600 litres of oil per hour compared to 3,500 for the F-16 fighters that they are replacing. As military systems have a lifetime span of 30 to 40 years, this means locking-in highly polluting systems for many years to come.

Moreover, military alliances like NATO have been clear that they will not compromise military dominance in order to tackle climate change. Climate change, in different national security plans, remains as much a call for increased military spending to deal with this ‘threat’, rather than a challenge to reduce or rethink their operations.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has super-charged military spending and emissions

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, and especially the huge escalation since February 2022, has been used to approve major increases in military spending (and, therefore, GHG emissions), with no signs that either Russia or the 30-strong NATO alliance have even considered the climate impacts.

- The European Commission anticipates a spending boost by its member states of at least €200bn, based on combining ad hoc extra funds and longer-term structural increases. The US has approved a record $840bn military budget for 2023, and Canada in 2022 announced an extra $8bn for the next five years. Russia has approved a 27% increase in military spending since 2021, which will bring budgets to a total of $83.5bn in 2023. Climate goals have been quickly thrown out of the window when it comes to military objectives. In 2022 alone, 476 of the most gas-guzzling fighter jets, the F-35, have been ordered – 24 for the Czech Republic, 35 for Germany, 36 for Switzerland, six extra for the Netherlands on top of prior orders, and 375 for the US.

- The war is already diverting resources from climate finance to military spending. In June 2022, the UK shifted money from its climate finance budget to partially finance a £1bn military support package for Ukraine. The Norwegian government has paused all disbursements of development aid, including climate finance, to get an ‘overview’ of the potential consequences of the war in Ukraine.

The biggest winner of this military spending bonanza is the arms industry

The arms industry has boomed from the global increases in military spending, as well as from diversifying into sectors such as border control and immigration management. The European Defence Agency (EDA) reported in 2021 that ‘the procurement of new equipment has benefitted most strongly from the overall increase in defence investments’ in recent years. After Russia’s full- scale invasion of Ukraine, and in particular the German announcement of €100bn extra spending, share prices of large arms companies have skyrocketed.

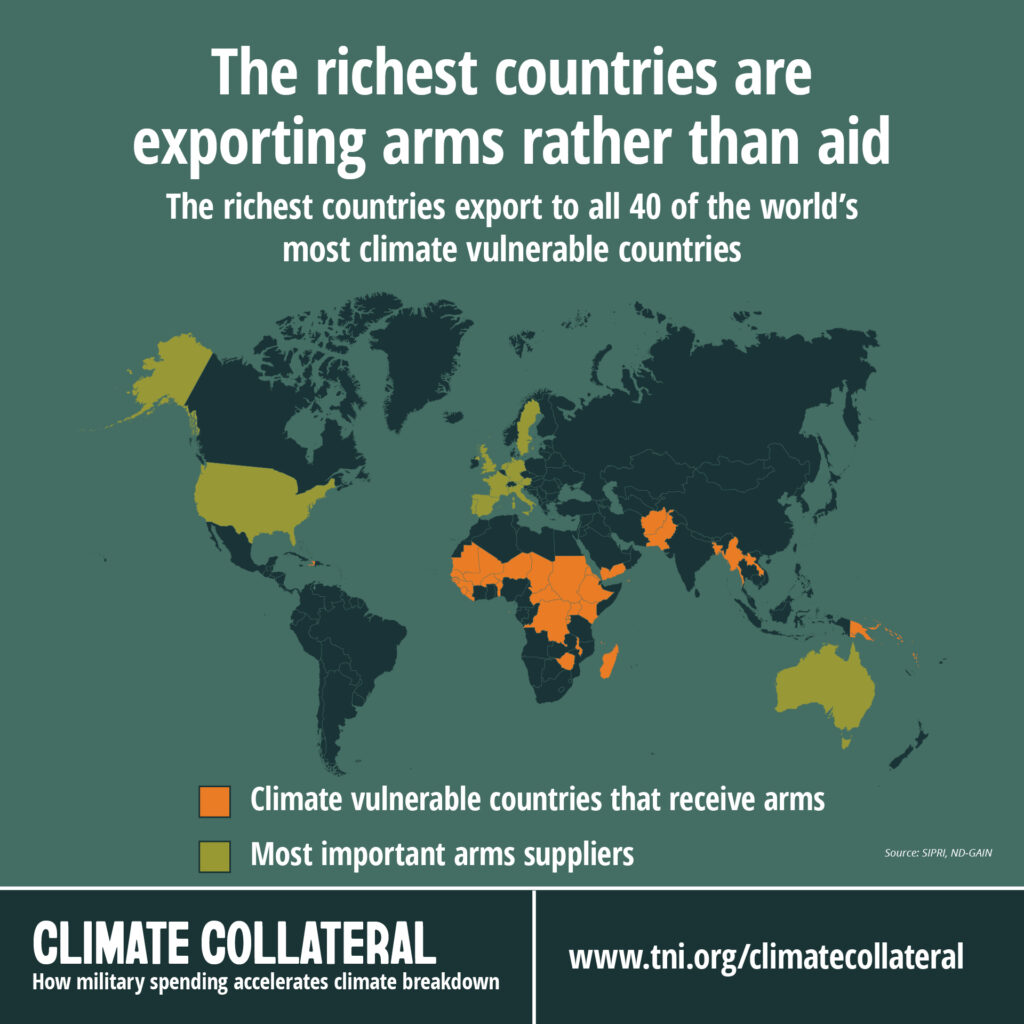

The richest countries are exporting arms to the most climate-vulnerable countries, fuelling conflict and war amid climate breakdown.

- The richest (Annex II) countries accounted for 64.6% of the total value of international arms transfers (2013–2021).

- Annex II countries have exported arms to all 40 of the most climate-vulnerable countries. Thirteen of these countries are involved in armed conflicts, 20 have authoritarian regimes and 25 are among the countries with the lowest levels of human development. Some of them are also subject to UN and/or EU arms embargoes (Afghanistan, Central African Republic, Myanmar, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen, and Zimbabwe).

- Russia and China, the second and fourth biggest arms exporters, also export to climate- vulnerable countries and are known for ignoring international arms embargoes. Between 2013 and 2021, China has exported to 21 and Russia to 13 of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries.

These arms exports not only divert money that is needed to instead mitigate and adapt to climate change, but also run the risk of fuelling conflicts, repression, and human rights abuses for populations on the frontlines of climate change. This is a form of climate maladaptation.

Egypt is one of the many countries supported with arms deals rather than climate action

Egypt will host the UN climate talks, COP27, in November 2022, but it is much better known for its military spending than for its climate action.

- Between 2017 and 2021, Egypt has been one of the top five arms-importing countries, receiving 5.7% of global imports. Its main suppliers are Russia (41%), France (21%) and Italy (15%). It also receives support for its police and border guards from EU member states, particularly Germany.

- Yet Egypt has entered into deals for fossil fuels worth $74bn since 2014, including with US companies like ExxonMobil and Chevron, has failed to develop effective climate adaptation plans, and is actively repressing climate and democracy activists in the country, including in the run-up to COP27.

Military spending could pay for a global Green New Deal

The richest countries have consistently failed to meet their promises to provide an insufficient $100bn a year in climate finance to the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries. And they refuse to make any concrete commitments to pay for mounting loss and damage, such as the floods in in Pakistan and the drought in the Horn of Africa in 2022.

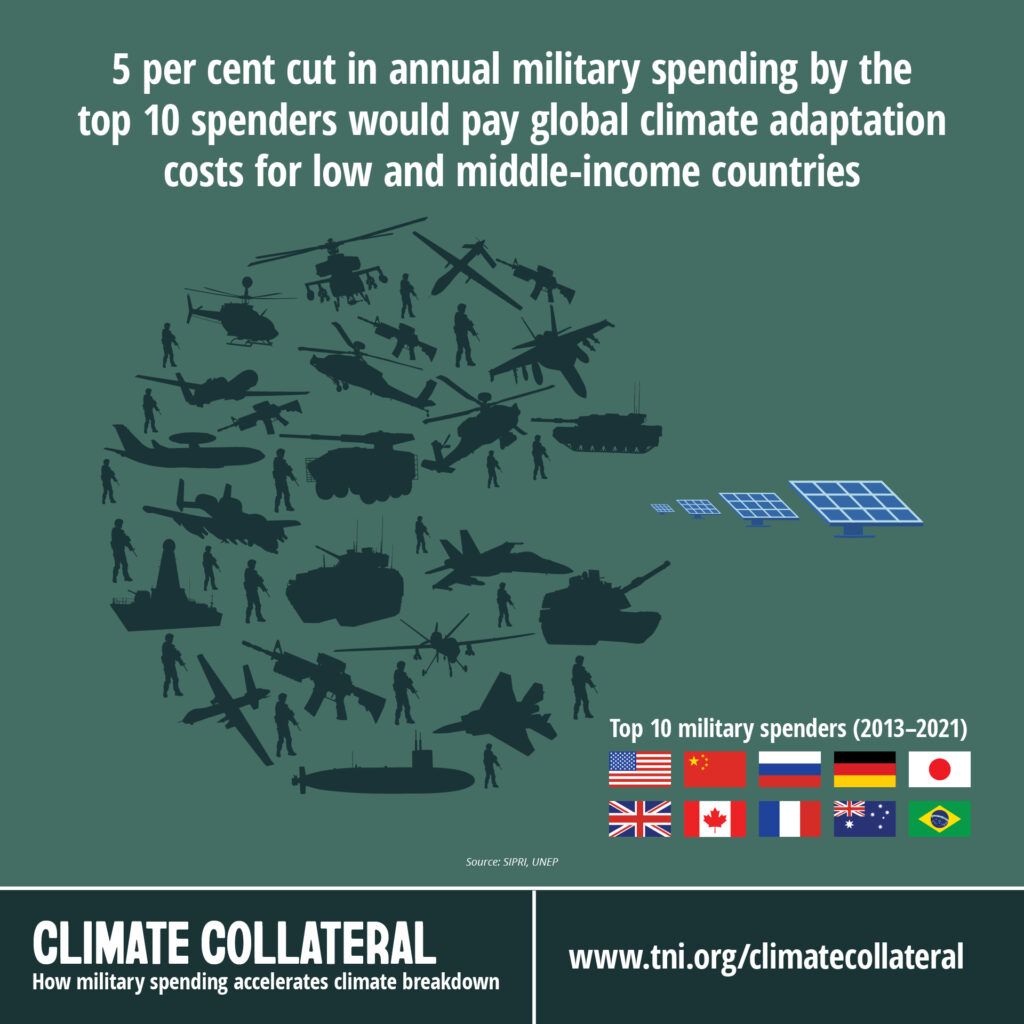

- One year’s military spending by the top 10 military spenders would pay for promised international climate finance for 15 years (at $100bn a year).

- $70bn of climate adaptation could be paid with just 4% of what the top 10 (USA, China, India, UK, Russia, France, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Japan and South Korea) spend annually on the military (a ratio of 1:23) and 3% of annual global military spending (1:30).

- Together with other proposals for financing – such as an end of fossil-fuel subsidies, disbursement of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), new taxes on fossil-fuel extraction, financial transactions, aviation and shipping – there is more than enough money to fund mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage.

Faced with the climate crisis and the signs of reaching dangerous planetary tipping points, there is an overriding imperative to prioritise climate action and international cooperation to protect those who will be most affected. Yet in 2022, an arms race is exacerbating the climate crisis and preventing its resolution. It could not come at a worse time. To tackle the biggest threat to human security, the climate emergency, we need all countries – NATO members as well as Permanent UN Security Council members Russia and China – to work together to prioritise climate over militarism. There is no secure nation without a climate-secure planet.

Download the full report here.

The executive summary is available in English, Spanish and Catalan.

Find out more at the TNI website.

Please share this report, and feel free to also use these social media graphics: